History of the Netherlands (from 1506 – Present)

This article was written with the expressed intent to engage your interest in learning more about the rich history of the Netherlands. While I’ve attempted to paint a general picture of the journey the history of the Dutch culture has taken since the 16th century and onward, I’m sure some very important events were left out. That being said, this should serve to bring you up to speed on how the Netherlands has come to be what it is today: a breathtakingly beautiful country, steeped in a rich, flavorful and colorful history. Enjoy.

The Netherlands Up To This Point

Our story begins in the 16th century, but the Netherlands origins travel much farther back than that.

The earliest known human life to inhabit the area now known as the Netherlands did so some 40,000 years ago. At the time, the people were hunter-gatherers and roamed across the country for wild game. The first settlements didn’t begin to appear until around 4800 B.C.

Several centuries later, during the Iron Age (800 B.C. – 58 B.C.), the area began to prosper thanks to the availability of iron ore in the area. This prosperity garnered the interest of the early Romans, and they took over the area starting in 57 B.C.

The Romans ruled over the Netherlands for 450 years, influencing the citizens of the Netherlands in a grand way. Towns were built, new settlements founded, and new military structures constructed. The influence of the Romans would affect the citizens for generations to come.

The Early Middle Ages (411 – 1000) would see many achievements in the Dutch culture. It was during this time that the Frisian Kingdom was established, the Dutch language emerged, the first Christians settled into the area, and the Vikings raided the Low Countries.

The High Middle Ages (1000 – 1432) saw the Netherlands become part of the Holy Roman Empire, and accompanied with the continual war between feuding states. Holland established itself as a major area of influence, and saw many wars between 1350 and 1490, mainly over the title of count of Holland.

The Burgundian period (1433 – 1567) was begun when the Duke of Burgundy united much of what would become the current day Netherlands and Belgium. It was the period when the

Dutch’s road to nationalism began. And it’s also where our story begins.

The Reign of Charles V (1506 – 1555)

Charles V, at the tender age of six, inherited the Low Countries after the death of his father, Philip the Handsome. However, due to his young age, his aunt, Margaret of Austria, would govern his kingdom until 1515, when he became of age.

By 19, Charles V had become the Emperor of not only the Spanish Empire, but the German Empire as well. He wouldn’t come back to the Low Countries until the death of his aunt, when he then needed to appoint a new regent for the area, his sister, Mary of Hungary. Under the guise of helping his sister, due to her lack of experience, Charles established several councils to assist her. But the real motive behind the counsels was to recruit potential opposition into his camp.

Charles was ambitious and determined to extend his empire. As a result, he was always at war with new countries and busy defending the ones he had already acquired. One of the countries he was constantly in conflict with was France. With the Low Countries bordering France, they became a central location for wartime efforts, which created unrest in the region.

Charles V’s reign ended in 1555 out of his own choosing. He was tired and weary from the years of war, so he abdicated his throne and gave the Spanish Empire (including the Low Countries) to his son, Philip II, and the Roman Empire to his brother, Ferdinand.

The Eighty Years War and the Dutch Republic (1566 – 1648)

The Start of the Dutch Revolt

During Charles’ reign and afterwards, specific laws made it acceptable to persecute and execute Protestants. As a result, several nobles from the Lower Countries paraded through the streets of Brussels to peacefully petition for better rights for Protestants.

Margaret of Parma was Governor of the area at this time, and she suspended the laws while she sought counsel from Philip II. During the period that the laws were suspended, several Protestants began attending public ceremonies. It wasn’t long before an especially inspired speech resulted in a small uprising, where several Protestants stormed a local monastery and defaced it.

This particular event didn’t occur out of the blue, but as a result of years of pent up tension and aggression between the Protestants and the Catholics. Add to that the fact that the area was facing an economic crisis, and social unrest was inevitable.

After gaining word about the destruction of the monastery, Philip II ordered the Duke of Alva to the Netherlands to stop the unrest and establish Spain’s authority over the population. And Alva did just that, in his own unique and terrible way.

The Duke of Alva established the Council of Troubles, which became known as the Council of Blood, because of its many death sentences against those involved in the attack on the monastery.

Alva thought the Council would take care of the unrest in a few short months; however, it would be years before the fallout from this conflict would reside.

War Breaks Out in the Netherlands

It wasn’t long before Alva was appointed Governor over the Lower Countries, which sparked even more unrest from the citizens of the Netherlands. It wasn’t long until Alva was sending Spanish troops to different cities to “reprimand” citizens for declaring for the prince, with one of the worst incidents being the execution of some 500 Protestant rebels in the town of Zutphen by way of drowning in the frozen River Ijssel.

Other towns were surrounded and forced into starvation. And once starvation took hold, the towns would surrender to the Spaniards only to be executed in droves, and in very excruciating ways.

The first victory for the Netherland citizens came during the siege of Leiden, which lasted an entire year from 1573 to 1574. The Spaniards had surrounded the city, and over a third of the population had perished. But victory finally came in the form of William of Orange and his troops when they marched out to meet the Spaniards. The Spaniards eventually retreated and herring and white bread were brought into the starving city. The event is still celebrated today.

Rebels Rally Around Prince William of Orange

After the Leiden siege had ended, William of Orange had inherited a staunch following of rebels and rebel supporters. His attention was then turned towards diplomacy and uniting all of the provinces to form an alliance against Spain. That alliance became a reality for a short while in 1576, after the Spaniards went on a rampage in Antwerp. However, the alliance would only last for three short years.

By 1579, the provinces had divided themselves into two separate factions: the Protestant North and the Catholic South. The North stayed with Prince William while the Spanish fought to win over the South.

Maurice, the New Hope

William of Orange was assassinated in 1584 after King Philip II declared him to be an outlaw. After William’s assassination, his son, Maurice, took over the operation. It wasn’t long before he made a splash in the offensive.

The Duke of Parma was advancing into northern territory, going as far as Antwerp in 1585. Upon news of the taking of Antwerp, Queen Elizabeth I of England became concerned about the momentum of Spain’s military campaign, and sent her own army, led by Earl of Leicester, to assist the rebels in their wartime efforts.

The English had little success until 1588, when the tides drastically switched towards the English and Maurice’s rebels favor, after the English gained victory over the Spanish Armada. Soon after, the Dutch launched their first offensive against the Spanish.

Maurice and his cousin, Willem Lodewijk, led the Dutch to a series of victories over the Spaniards, starting with the siege of Breda in 1590. This string of victories would continue for the next eight years, and culminate in the Spanish king’s abandonment of the Netherlands’ government in 1598.

For the next 11 years, several battles were waged and sieges commenced between the Dutch and the Spanish. Hundreds of thousands of lives were lost, but the conflict would finally come to an end after several naval victories by the Dutch. In 1609, both parties agreed to what would be called the Twelve Year Truce.

Conflict During the Truce

You would think that after all of the bloodshed that was had at the hands of the Spanish armies, the Dutch would welcome years of peace and harmony after the Twelve Year Truce. Unfortunately, new conflict was already in progress, and it was between the church and the state.

The conflict started with a debate about predestination between Jacobus Arminius (against predestination) and Franciscus Gomarus (for predestination). This dispute eventually became a nationwide conflict, and Dutch citizens began to take sides, including its leaders.

Maurice of Orange and his followers supported Gomarus and became known as Counter- Remonstrants, and Grand Pensionary Johan van Oldenbarnevelt sided with Arminius, whose group became known as Remonstrants.

The conflict split the provinces in two and caused several internal conflicts until 1618, when Maurice commanded the arrest of van Oldenbarnevelet. Thanks to Maurice’s connections within the provinces, a special court was created and decided van Oldenbarnevelet was guilty of treason and was sentenced to death. After the conflict was over and van Oldenbarnevelet was executed, Maurice would never again achieve the popularity he once had with the Dutch population.

The End of the Twelve Year Truce and the Eighty Years War

In 1621, the Twelve Year Truce ended, and war between the Dutch and the Spanish picked up where it had left off, with both armies fighting to claim new territories and defending existing ones. In 1625, Maurice of Orange died, and Frederick Henry, his half brother, gained control of the Dutch army.

Frederick Henry developed a reputation for successfully conquering Spanish-occupied cities. In 1635, he joined forces with the French to regain control of several key Southern Netherlands provinces, including Breda. The Dutch Republic was gaining strength, and they were proving to be a heavy burden for the Spanish empire.

Over the next decade, the two sides battled on – the Spanish having to deal not only with conflict in the Netherlands, but also around their home country of Spain. The Dutch, on the other hand, faced an impending economic crisis due to years of funding the war. Both sides were growing increasingly tired of the conflict. The end was at hand.

The Treaty of Munster took place on January 30, 1648, officially ending the war between the Republic and Spain. The Eighty Years War was over, and the Netherlands had its own sovereignty at last.

The Dutch Republic’s Golden Age (1600 – 1690)

Explosive Growth in Amsterdam

Even during the conflict between the Dutch and Spaniards, Amsterdam was experiencing growth like never before. By 1600, it had already established itself as a trade and shipbuilding epicenter. Due to the success of Amsterdam, immigrants flocked to the area on a daily basis. Amsterdam was the city of opportunity, and people of all types were attracted to it.

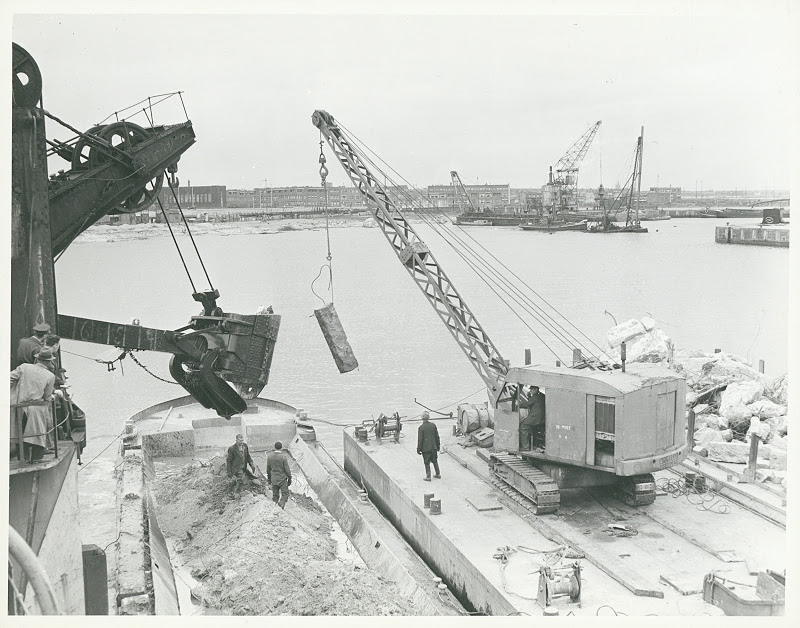

Up until 1613, Amsterdam had contained itself within the borders of the canal that surrounded the city. By that time, the city was overflowing with new occupants, and was essentially forced to expand its boundaries. Three new canals were constructed around the city with each new expansion, and that’s how Amsterdam’s ring of canals was formed. These canals would come to be the home of the rich and affluent of the city.

During this period, Amsterdam gathered all of its wealth due to the massive trade market and shipbuilding. Products from all around the world were brought to the area, packed and sold, and eventually shipped to its new destination.

The First Jews Arrive in Amsterdam

The Golden Age saw the first Jews arrive to the Netherlands from Spain and Portugal. Most of the Jewish immigrants settled in Amsterdam, where, at first, it was prohibited to openly practice their faith. However, it wasn’t long before they had constructed a simple synagogue near a canal in the city. Due to their importance to the city (many were wealthy merchants), authorities tended to turn a blind eye to the newly constructed synagogue.

Then, in the mid-17th century, the prohibition was lifted, and the Jews were able to freely and openly practice their religion. The Portuguese Jews constructed an elaborate cathedral in the middle of the city, the Esnoga, which still functions to this day, while droves of Easter European Jews flooded into the city and its surrounding areas.

The Anglo-Dutch Wars

While the Dutch economy and society were experiencing a Golden Age, war was always on the horizon, and the first of what would become a series of three wars called the Anglo-Dutch Wars was underway in 1652. It consisted of eight major battles with the last one being a vicious naval battle that found both sides ravaged and unwilling to continue. A peace treaty was signed in 1654, and the First Anglo-Dutch War was in the books.

Only a mere decade later relations between the English and the Dutch had once again deteriorated. Naval war broke out, and culminated with the Dutch fleet, led by Admiral Michiel de Ruyter, destroying several of the English’s docked ships and taking England’s flagship vessel, the Royal Charles. The English had no choice but to sign another peace treaty, and the Second Anglo-Dutch War was in the books.

The Third Anglo-Dutch War took place between 1672 and 1674, and centered on the French trying to invade the Dutch provinces. The English allied with the French; however, their trust in each other was lacking, to say the least, and as a result the French failed in landing an army on Dutch land. And the Third, and final, Anglo-Dutch War was in the books.

The Intellectual Boom

It was during the Golden Age that scientists, mathematicians, and intellects from all over the world flocked to the Netherlands, thanks to its intellectual tolerance. Famed French philosopher and mathematician, Rene Descartes, had some of his most important works published in Amsterdam during this period.

Christiaan Huygens discovered Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, invented some of the most powerful telescopes of their time, explained Saturn’s planetary rings, and invented the pendulum clock – all within this period of discovery and learning.

Other famed philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists, like Locke, Hobbes, and Spinoza were all involved in one form or another with the Netherlands during this period of massive intellectual growth.

William of Orange, Stadholder and King

Towards the end of the Golden Age, stadholder William III made a run at the English crown, which at the time belonged to his wife’s father, King James II. William’s wife, Mary Stuart, was the next in line for the crown until James had a son, and decided to raise him to take over.

King James II’s opponents urged William III to dethrone his father-in-law, and that’s exactly what William set out to do. Upon William’s arrival in England, James fled to France; but the fight was not over. Fighting lasted for the next couple of years, and culminated in 1690 with William’s decisive victory at the River Boyne.

William’s rule as both king of England and stadholder lasted for 12 years, and saw a rift form between France and William’s empire. During this time, France was eager to join with Spain. England and the Netherlands joined forces to try and prevent that union from occurring. The two groups of allies soon went to war with the other.

Shortly after the war started, William III died in a freak horse-riding accident. Since he had no heirs and his wife was deceased, the Netherlands had a decision to make about their new stadholder. Their decision was to forego a new stadholder for now, and they governed themselves.

The war effort continued on and the Dutch and English shared quite a few victories together; however, it proved to be a very bloody war for the Dutch Republic. In the end, the English and the Dutch succeeded in preventing the union of France and Spain; but the Netherlands was practically bankrupt from the cost of war. Their gains were few, the Golden Age was officially over, and they were broken as a country. Unfortunately, it would remain that way for quite some time.

The Patriots Come to Power (1781 – 1795)

As the Golden Age ended, the Netherlands were in a perpetual state of turmoil for several years, largely due to the economic struggles that accompanied the procession of wars that plagued the country throughout the 17th century. The country was upset with the current state of things, and the winds of change were beginning to blow.

On a night in September 1781, a small pamphlet was passed throughout the city to all who would read it. This pamphlet served as a calling card for the people of the Netherlands to take back their roles in the government of the country. Greater individual rights were demanded, and this sect of the population would stand for nothing less. This population would come to be known as the Patriots, to signify their love for their country, and they would make a very big splash in the years to come.

The Patriots criticized and blamed Prince William V of Orange for the corruption, discrimination, and abuse that currently existed in the government. And Prince William V, in response to this criticism and growing unrest, decided to flee to Gelderland with his wife, Wilhelmina, in 1785.

The supporters of William the Orange (the Orangists) stayed the cause and fought back against the Patriots allegations. Soon, turmoil and conflict became rampant throughout the surrounding areas. The conflict started with open debates and finger-pointing in various publications and pamphlets, but soon escalated into violence. In 1787, things took a turn for the worse.

An incident involving Princess Wilhelmina occurred in which she was refused passage to The Hague at gunpoint by Patriots, out of fear of her arousing Orangist supporters. As a result of this insult to his sister, King Frederick William II of Prussia sent his army to squash this Patriot rebellion for good. It worked, and by the end of 1787, approximately 40,000 Patriots had fled to the safety of France.

But the Patriots weren’t finished… yet.

Seven years after the Patriots fled the country, help arrived in the unlikeliest of places, France. The French Revolutionary army arrived on Dutch soil in 1794, and forced William V to flee again, this time to England. After the French army had “cleared the way”, the Patriots returned to their homeland, and were able to easily gain power over the country.

The Batavian Republic and French Takeover (1795 – 1813)

The Batavian Republic

January 18, 1795 marked the beginning of the Patriot’s takeover of the administration in Amsterdam. The next day the revolutionary Batavian Republic was established under the watchful eye of the French, and brought with it equal rights to all citizens, in addition to the formation of elected representatives.

The French Take Over

The Batavian Republic remained in power until 1806, when Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte appointed his brother, Louis Bonaparte, as the first King of the Netherlands. However, it was an ill-fated appointment, and one that would last for only four years. In 1810, Napoleon removed his brother from power and annexed the Netherlands to France.

Netherlands: The Kingdom (1810 – 1848)

In 1813, a provisional government was created to gain power of the country back from the French. In this government, William V was able to make his return back to the Netherlands. After 18 years of exile, William V returned and was coroneted in Amsterdam as the sovereign prince.

North Netherlands and South Netherlands were combined to serve as a fortified barrier from neighboring France, and the Netherlands was deemed a kingdom by the constitution, which was constructed in 1814. Very shortly after, William V named himself King William I.

King William I worked to rebuild what the French had destroyed during their occupation of the country. He was adamant in reviving the Dutch economy again, rebirthing the trade and industrial industries.

All was headed in the right direction until Napoleon showed up for one last hoorah.

Napoleon Returns and the Battle of Waterloo

As soon as Napoleon could find a way back into France, he capitalized on it. Upon his return from Elba, the island to which he was exiled in 1815, Napoleon quickly won over the French military, forcing King Louis XVIII out of the country.

Naturally, this set off warning signals for all of the major European nations, and they decided they needed to act swiftly and not allow Napoleon the opportunity to rebuild his empire. The English, Dutch, Austrians, Prussians, and Russians all marched to the border of France to engage Napoleon’s forces, but to no avail. Napoleon wasn’t there, and was already advancing his campaign.

Napoleon had taken Brussels and was planning his next piece of the strategy when he was met at the Brussels border by an Anglo-Dutch army, led by the Duke of Wellington, and accompanied by the prince of Orange (King William’s son). Victory seemed to be in Napoleon’s grip until the Prussians showed up in the midst of battle. Shortly after their appearance, Napoleon and his army were finished for good.

The Belgian Revolution

Napoleon was no longer an issue, but, as usual, new conflict was waiting just around the corner – this time in the form of the ruler of the kingdom himself, King William I.

King William practiced complete authoritarian rule over the country, and as the years passed by, social unrest began to rear its head. This time it was coming from the citizens in the Southern Netherlands.

To try and stop the unrest, the king sent his two sons to Brussels to mediate and potentially establish a truce with the people. They were successful, but the unrest ultimately would not cease. And in 1831, William I decided to try an end it using brute force.

Troops were sent to the Southern Netherlands on August 2nd and battles ensued between the Belgian “rebels” and the Dutch army for ten days. On August 12, on the cusp of defeat, 70,000 French soldiers came to fight alongside the Belgians and force prince William of Orange and his army to retreat. The fighting ceased that same day.

The war with Belgium would last another eight years until the Treaty of London was signed between the Dutch and the Belgians in 1839. In 1840, King William I abdicated his throne to prince William of Orange, who from then on became known as King William II. The new king, however, was coming to power at the dawn of a revolution – one that would sweep the entire continent.

The Times are Changing (Constitutional Monarchy)

By 1848, King William II had become somewhat of an expert at overruling proposed changes to the constitution. He enjoyed his absolute monarchy and was not interested in relinquishing it. However, the people of the Netherlands didn’t quite feel the same way.

The French king had already abdicated his throne, and the French republic was subsequently born. The Dutch were after the same thing. For fear of being thrown out by one means or another, King William II backed the amendment of the constitution, and Johan Rudolf Thorbecke drafted the constitution of 1848. The Netherlands was now officially a constitutional monarchy.

Although it has been revised several times since, the constitution that was drafted in 1848 still stands as the basis for the operation of the Dutch government to this very day.

The Industrial Revolution (1850 – 1918)

The mid-19th century saw the rise of industry in the Netherlands, and a drastic decline in working conditions for the working class. As you can imagine, social unrest (and reform) was soon to follow.

But before the working class received their due, there was another part of the population that needed to be given their rights back – the slaves.

Abolition of Slavery

Slavery, at this point, had been a part of Dutch society for centuries. It wasn’t until the late 18th century that citizens began to wise up to the injustice of this terrible practice.

The Netherlands had stopped and outlawed their slave trade practices by 1814, but slavery itself was still in full effect, and it would continue for several more decades. Finally, on July 1, 1863, slavery was abolished in the Dutch colony of Surinam. But it wasn’t quite over for the slaves.

The abolition did make the slaves free, but plantation workers were required to continue working on the plantation for another ten years per a contract. The slaves were officially free, but it was a ludicrous final price to pay for freedom.

Labor Laws and Unions

At the beginning of the Netherlands’ industrial revolution, child labor and excessively long workdays were in full force. Twelve year olds (and sometimes younger) frequented the workplace, and twelve-hour workdays were the norm. Members of the community began to take notice, and they were passionate about change.

One of these members was Samuel van Houten, a member of parliament, who initiated legislation in 1874 that would make it illegal for children under the age of twelve to be employed in factories. However, the legislation was not closely administered and child labor, while declining slightly, was still going strong.

Future laws were passed in 1889 and 1911 that would regulate the number of hours women and children could work, as well as further enforce the child labor laws set forth in 1874.

Unions also became an integral part of Dutch society during the industrial revolution. Workers banded together to seek more rights and better working conditions from their employers. This was particularly common with factory workers, who seemed to get the short end of the stick most often.

Rails and Steam

The introduction of rail travel was slow to catch on in the Netherlands, but when it did, in the mid-19th century, it did so in a big way. The railways practically exploded overnight, and a rail system was being constructed all throughout the country. This rail system also called for new bridges, which were constructed in factories that were now using steam to operate their machinery.

The steam engine was in full force during the industrial revolution. Steam-powered ships replaced sailboats. And steam became the major source of power in factories across the nation.

This modernization of Dutch industry led to drastic increase in another area – the population. By 1900, 500,000 citizens resided in Amsterdam alone – 300,000 more than in the first half of the 19th century. In response to this new burst of growth, a new housing boom was begun, one of the fastest in Dutch history.

World War II (1940 – 1945)

Germany Invades the Netherlands

Beginning on May 10, 1940, and lasting only five days, the German Nazi army invaded the Netherlands by air and land. The attack began in The Hague, and within a few hours, Germany had control of the northern provinces. However, the Dutch weren’t yet ready to give up.

They drew a defensive position in Utrecht where the Germans eventually engaged them in intense fighting. The Germans quickly took the upper hand. The Dutch, realizing they had no chance of defeating the Nazi army, surrendered on May 14. All total, over 4,000 Dutch citizens lost their lives, and an additional 2,700 were wounded.

Germany had taken the Netherlands, and the worst was yet to come.

The Holocaust

It started with segregation and isolation. Shortly after Germany gained control of the Netherlands, the Dutch Jews were prohibited from entering most public places. On top of that, they were dismissed from certain jobs, and their children weren’t allowed to attend school.

By 1942, they were forced to wear a yellow “star of David” on their clothes, so to be distinguishable from the rest of the population. The badge was used not only to humiliate and degrade the Jewish citizens, but also to help control their movements and keep tabs on them. The worst was still yet to come.

The worst came just a couple of months after the Dutch Jews were forced to wear the “star of David.” Deportations to concentration camps began, and wouldn’t cease until September 1944. Approximately 107,000 Dutch Jews were deported to these camps, and most perished there.

Over six million Jews ended up losing their lives in what would come to be called the Holocaust – one of the most terrible acts of genocide the world has ever seen.

The Dutch Resistance

As Germany’s treatment of the Jews became worse, the anger of the Dutch population greatened. It wasn’t long before Dutch resistance groups began popping up to either help hide Jews or aid the Alliance in bringing down the Nazi regime.

As the war waged on, these resistance groups would do increasingly bold acts to help the allies – assassinate German officers, blow up important methods of transportation, raid German-operated offices and factories, and more.

The Liberation of the Netherlands

After four long years of occupation by the Germans, the Netherlands was liberated. However, it didn’t happen overnight.

South Netherlands was the first to become liberated in the fall of 1944. The rest of the Netherlands became officially liberated on May 5, 1945, and on August 15, 1945 the Dutch East Indies would become liberated from Japanese occupation, thus ending the war.

Progress After the War (1945 – Present)

The Netherlands’ society changed drastically after the war. The country’s economy was in shambles and the people were still recuperating from the massive losses sustained during the war – both human and structural.

However, the Dutch are resilient, and are quick to bounce back. It wasn’t long until they were making great strides towards improving their country, rising to new heights of prosperity and happiness.

The 40s and 50s

Reconstruction began shortly after the war was over. The United States aided greatly in the Netherland’s recovery, providing goods, food, materials, and funds for the reconstruction effort.

Willem Drees extended the welfare state during this time. He ensured that the government took responsibility for the welfare of its citizens – providing the basic necessities needed for life. Public health services, financial benefits, and affordable education were all part of this new system.

The baby boom also occurred during this time. Young men and women had suffered through past financial turmoil and the terrors of war, and were now looking forward to a brighter future and a family of their own.

The 60s and 70s

The 60s and 70s marked a period of great cultural and social change throughout the world, including the Netherlands. The baby boomers were now teenagers and young adults, and they were all about rebelling against the establishment.

This younger generation became engaged in things like rock and roll, sexual exploration, drugs, idealism, and informal clothes. They wanted to distinguish themselves from the past generation as much as possible. And they were successful.

As of result of this youth movement, religion began to fade into the background of Dutch society. Neighborhoods, cities, and countries became more secular, and religion was discussed less and less public – a practice that is still widely in affect to this day.

The 80s and 90s

The 80s and 90s saw mass influx of immigrants come into the country followed by a mass blending of different cultures.

Starting as far back as the 60s, the Netherlands began letting foreigners into the country as guest workers, due to a shortage of laborers in the workforce. Their stay in the Netherlands was to be temporary, but several of them stayed and acquired permanent work permits.

This trend continued well into the 80s, and by the 90s a cultural melting pot was in place. Cuisine, customs, language, and religion were all brought in from countries like Turkey and Morocco, and became ingrained into the Dutch society, where they remain to this day.

The 2000s to Present

The 2000s saw a great political debate on integration of migrant workers into the Dutch society. That debate has seen more than its share of turmoil and strife, and continues to be an ongoing battle between political powers to this day.

However, the Netherlands has continued to prosper since the end of the war. The Dutch have evolved into one of the most accepting, egalitarian, and prosperous countries in the world, and they show no signs of slowing down anytime soon.